In preparing for a Sunday School class, I was reading the account in Genesis 3 of God’s interrogation and sentencing of Adam, Eve, and the serpent. I’ve read this passage many times before and am pretty familiar with it, but the English translation I was reading helped me notice something new. After Adam lays the blame for his sin on Eve (“the woman”) and even on God (“You gave to be with me”), Eve likewise blames her sin on the serpent. However, most translations render Eve’s confession as a simple statement of fact: “The serpent deceived me and I ate.” Thus, while Adam comes across like a cornered child defensively casting about for a scapegoat, Eve seems more calm and up front about her sin. That is, until you read the HCSB’s rendering: “It was the serpent. He deceived me, and I ate.” It’s not a huge difference, but by splitting Eve’s statement into two sentences, the first of which simply points the finger at the serpent, the HCSB makes Eve’s response sound closer in tone to that of Adam.

Because I was so used to the typical rendering of this verse, the HCSB’s rendering caught me by surprise and led me to ask, “Is that really what the Hebrew says?”

By the way, this is why it is always helpful to use a variety of translations when studying a familiar passage. When a translation departs from what you’re used to, it can expose you to nuances in the text you may have missed before. At the very least, it may prompt you to dig deeper.

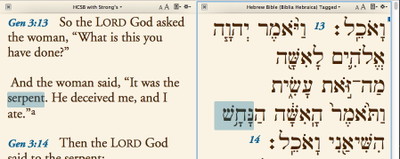

For me, digging deeper meant opening the Hebrew text in a parallel pane and examining Eve’s response. Cross-highlighting between my English Bible with Strong’s Numbers and the tagged Hebrew made identifying the corresponding Hebrew words incredibly easy.

The Hebrew simply has the noun “the serpent” followed by the verb “deceived” with the direct object “me”, which would seem to justify the typical translation of “The serpent deceived me.” How then, I wondered, could the HCSB justify rendering this simple sentence as two sentences? Were the translators taking liberties with the text?

Then I remembered that in Hebrew, the subject typically follows the verb. In cases like this, where the subject comes before the verb, the subject is generally being emphasized in some way. So the HCSB is not taking liberties with the text, but is bringing out a subtle nuance of the Hebrew which typically gets lost in translation: Eve’s emphatic pointing to the serpent as the one to blame.

Now, that naturally got me wondering where else the subject appears before the verb in the Hebrew Bible. In my next post, I’ll show you how to use the Construct window to find other occurrences of that construction.