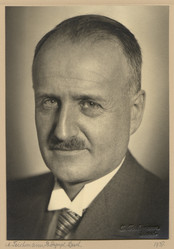

Walther Eichrodt (1890-1978) taught at University of Basel (Switzerland) from 1921-1966 where Karl Barth also taught. Previously, he had received his education at Griefswald, Heidelberg and Erlangen where, like Gerhard von Rad, he studied under Otto Procksch. He was a close colleague to Adolf Schlatter with whom he often led Bible conferences.

Walther Eichrodt (1890-1978) taught at University of Basel (Switzerland) from 1921-1966 where Karl Barth also taught. Previously, he had received his education at Griefswald, Heidelberg and Erlangen where, like Gerhard von Rad, he studied under Otto Procksch. He was a close colleague to Adolf Schlatter with whom he often led Bible conferences.

In 1933, Eichrodt broke with many of his recent teachers and peers by publishing Theology of the Old Testament (now in its 5th edition, 1960), affirming that the Hebrew Scriptures were not a substandard religious document, an idea that was in conflict with the prevailing German cultural mindset of the time. Throughout his life, although he remained a proponent of his contemporary understanding of an evolutionary origin to the Pentateuch as presented in the Documentary Hypothesis, nevertheless, he retained a very reverent view of the biblical text.

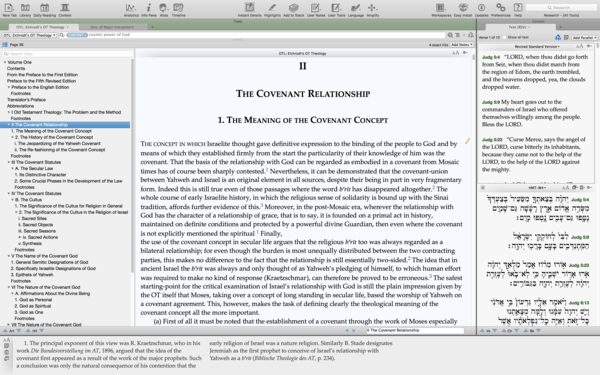

For Eichrodt, covenant (Hebrew: בְּרִית/bᵉriyṯ; German: bund) is the central theme of the OT. He defined covenant as God’s self-revelation in choosing people and how they should live (see ch. 2, “The Covenant Relationship” in vol. 1 for much greater detail than my summary here). Eichrodt suggests that covenant involves personal obligation of two parties, but the peculiar thing about biblical covenants was that God obligated himself. God’s covenant was mediated to Israel through charismatic leaders of their religious system. Covenant was so central to later events, that Eichrodt believed Moses and the events at Sinai to be historical, unlike some of his contemporaries at the time. According to him, Israel existed for the covenant, not the reverse. However, Eichrodt never quite reveals his view of exactly what happened at Sinai.

In choosing covenant as a central theme, Gerald Bray has suggested that Eichrodt was able “to uphold the doctrine of divine revelation, and to explain how God had been at work in the history of Israel” (Biblical Interpretation Past & Present, 1996, p. 386). Elaborating on the meaning of covenant, Eichrodt’s first explanation focuses on how the covenant delivered through Moses “emphasizes one basic element in the whole Israelite experience of God, namely the factual nature of divine revelation.” Eichrodt explains that “God’s disclosure of himself…[is understood]…as he breaks in on the life of his people in his dealings with them and molds them according to his will that he grants them knowledge of his being.”

For Eichrodt, textual development began with oral tradition. Behind these oral traditions were specific historical events. Then there was a pre-textual reflection on the events which led to the production of the written sources of the Documentary Hypothesis: JEPD. Eichrodt points out that words held more power in ancient times than in contemporary times. He writes of “the cosmic power of God.” For him, the word of God is linked to the Spirit of God.

As stated earlier, Eichrodt held to the central theme of covenant in his theology. Rather than using a book-by-book approach, Eichrodt uses systematic categories to discuss the theology of the OT. Having a central theme gives him a number of benefits. First, it offers an organizing structure to Theology of the Old Testament since everything in the OT must therefore—somehow—be related to covenant. This also allows him to relate very divergent texts to each other because they had the single common element of the covenant connecting them. Second, it stresses the unity of the OT, which could be seen as a work containing multiple sources focused upon the same theme rather than a work of divergent literature that only had nationality as a common element.

Of course, one could ask how to fit the ever-present issue of Wisdom literature to the central-theme approach. How does the Song of Solomon relate specifically to covenant? If Eichrodt focuses on one major theme, how well can he treat divergent themes in Scripture? To be fair, E. A. Martens writes that “Eichrodt did not ignore the diversity others saw in the Old Testament. However, he started with the notion of theological unity. Other scholars since Eichrodt’s time have been more enamored with theological diversity in the Old Testament.”

Regardless of the one’s opinion of a one-theme approach for the Old Testament, Eichrodt brought fresh understanding and insight into OT scholarship that arguably can still be wrestled with today. His two volumes on OT theology display not only his ability to communicate well, sometimes even poetically, but also they display his sincere devotion to God.

[Note: this blog post has been adapted from a review of Eichrodt’s Old Testament Theology that I wrote a few years ago.]