In Matthew’s Gospel (28:3), there’s a description of the clothing of the resurrected Christ stating they were “as white as snow” (λευκὸν ὡς χιών). But how would you communicate the concept of snow if it were foreign to another culture? Years ago, I remember reading in the UBS Translators’ Handbook, the following translation suggestion for this phrase:

White as snow is obviously going to be a problem in areas where snow is unknown. Some translators, recognizing that this is simply a way of saying that his clothing was very white, either use a cultural substitution such as “white as egret feathers (or, as cotton)” or use whatever is the normal way in the language to say “very, very white.”

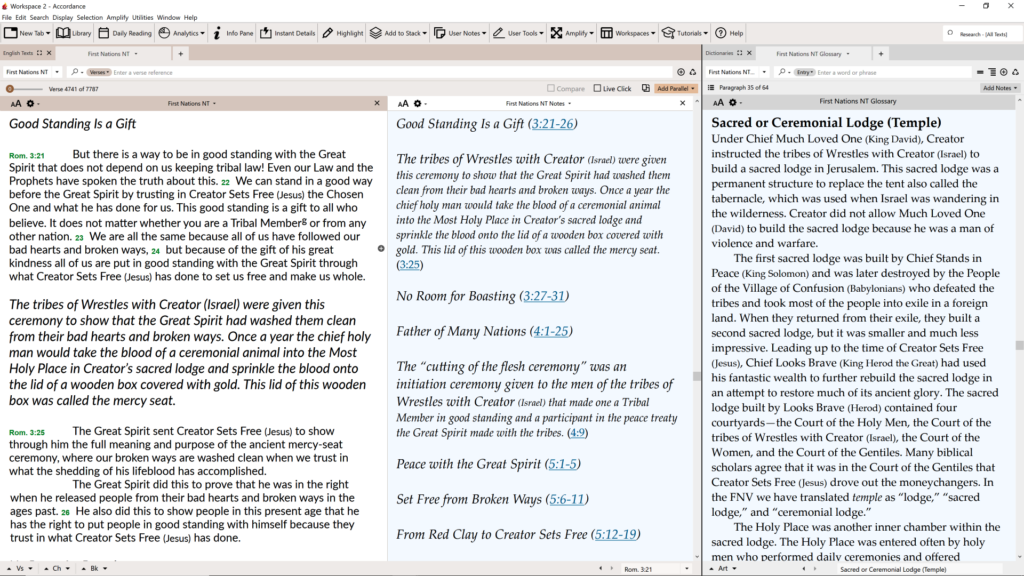

The above example illustrates how to communicate accurate meaning across cultural divides. I bring this issue up in introducing a new release for the Accordance Bible Software Library: First Nations Version: An Indigenous Translation of the Bible (FNV). As stated in the introduction, “The First Nations Version New Testament was birthed out of a desire to provide an English Bible that connects, in a culturally relevant way, to the traditional heart languages of the over six million English-speaking First Nations people of North America.”

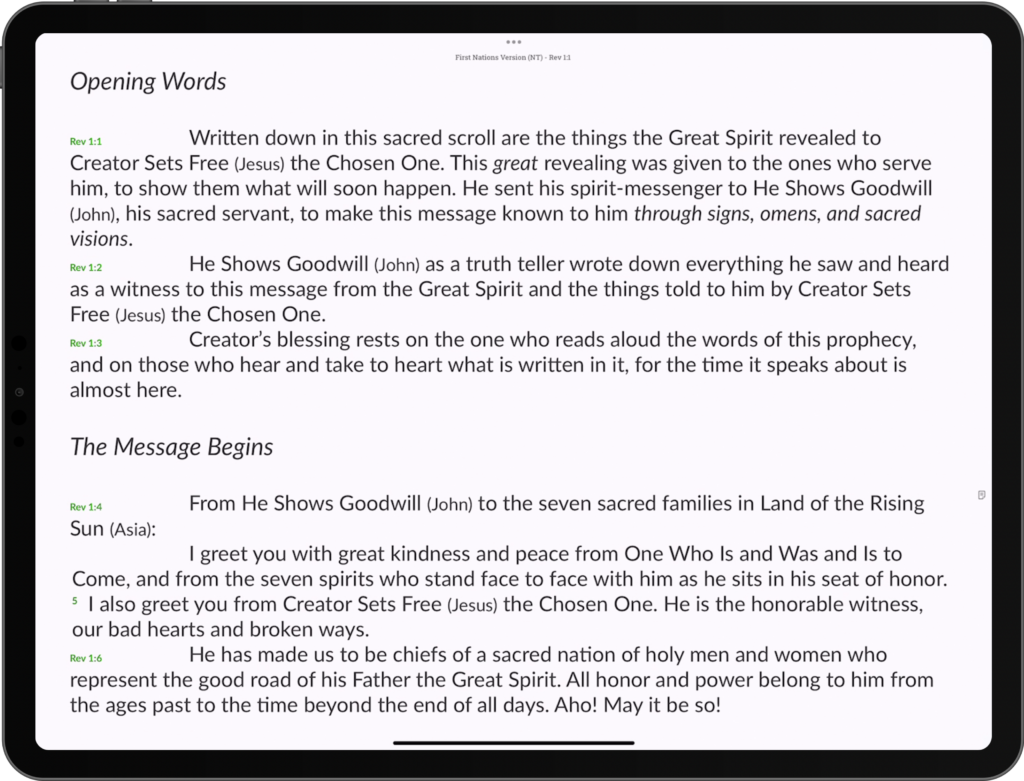

The FNV uses the story-telling methods and vocabulary of First Nations peoples (a.k.a. Native Americans) to present the New Testament message in a manner that is specific to the shared heritage of various English speaking tribes. And why English speaking? Unfortunately, over 90% of First Nations people do not speak their tribal language. However, many of them have experienced the traditional story-telling methods of their culture.

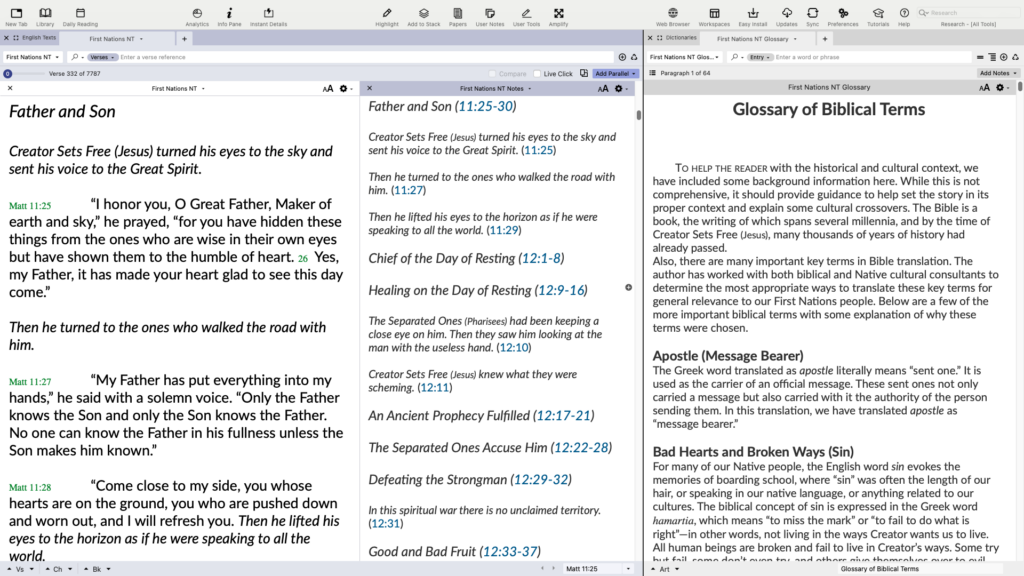

Readers familiar with traditional English Bible versions will quickly notice that familiar names, places, and events have been reworded to reflect a First Nations perspective. Here are a few examples:

- Great Spirit (God)

- Creator Sets Free (Jesus Christ)

- Bitter Tears (Mary)

- Small Man (Paul)

- Stands on the Rock (Peter)

- Gift of Goodwill (John)

- Father of Many Nations (Abraham)

- Village of Peace (Jerusalem)

- Sacred Lodge (the Temple)

- Wisdom Keeper (rabbi)

- Evil Trickster (the devil)

Traditional names are always included in parentheses after Native naming traditions such as in the examples above. Moreover, there’s an entire “First Nations Glossary” module for some of the renamed biblical designations that require further explanation. Italics are used for additional content that gives clarification to the text. Some of the expanded explanations are similar to what is often experienced in a study Bible.

Although this Bible version is very different from what most English Bible readers have experienced, there are solid individuals and organizations behind the FNV. The translation was first envisioned by Terry M. Wildman (see him in the video at the end of this post). He formed a “First Nations Version Translation Council,” the members of which are listed in the introduction. The FNV has the backing of prestigious partners such as OneBook, Wycliffe Associates, and Rain Ministries. The print version is published by InterVarsity Press.

The FNV is a creative effort to put the New Testament’s message in the vocabulary of specific indigenous cultures of North America. If you find yourself looking at the example passages in the screenshots of this blog post, and the FNV does not speak to you, realize that probably you are not the primary target audience for this translation. However, even if you’re not the target audience, you may find that in reading the FNV and seeing the New Testament through the lenses of a particular culture, you may gain new insights into the Bible’s message that you have never seen before.

For more information about the First Nations Version and the translation philosophy behind it, check out the official FNV website.