Did you know lexicon literally means “book of words”? If you use Accordance to study or read the Hebrew Bible or Greek New Testament, you know how valuable a good lexicon can be. I took my first biblical language class in 1992 and assumed at the time that in a few short years, I’d have both Greek and Hebrew mastered and eventually would never need to consult a lexicon again.

I wish I could tell you that my naive assumptions all those years ago had become a reality by now, but it’s simply not the case. In fact, my initial print lexicons became quite worn until I eventually switched to the electronic lexicons available for Accordance. Now, as I continue to use these tools, I’ve come to appreciate them even more than simply “dictionaries” to look up words that I don’t know off the top of my head.

At some point I realized that learning a biblical language meant more than memorizing the vocabulary lists in the grammar books. Learning a language is not simply learning a word-for-word correspondence with the words of my native tongue. And that’s where lexicons—“books of words”–come in. A good lexicon reveals to us the nuances for how words are used in different situations and contexts. And as I’ve gradually ventured to Greek and Hebrew writings beyond the biblical texts, I’ve learned to appreciate having not just a good lexicon, but having specialized lexicons.

Many Accordance users gravitate to some of the current standard lexicons, such as BDAG for New Testament Studies and BDB or HALOT for the Hebrew Bible. But have you ever taken a look at some of the other lexicons that are available? Here are a couple of examples.

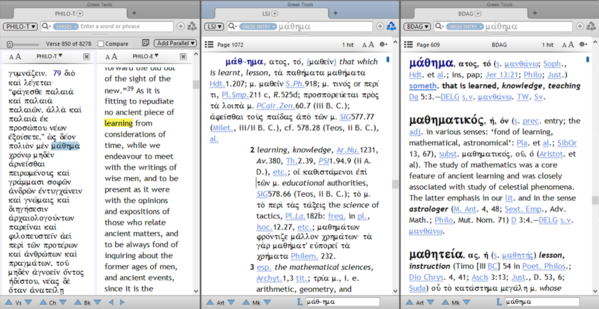

Liddell Scott & Jones Complete (LSJ). Maybe you’re reading in Philo, and you notice that every once in a while, the writer uses a particular word such as μάθημα, which the Instant Details reveals to mean knowledge, teaching, or lesson. This word doesn’t occur in the New Testament (although it does appear in the LXX). BDAG has an entry for the word, but it’s a bit short, so it would be nice to know a bit more. This is where the LSJ comes in handy. The LSJ is described as “the most comprehensive and up-to-date ancient Greek dictionary in the world.” Whereas BDAG’s focus is on New Testament and early Christian literature, the LSJ covers all ancient writing in Greek.

So, yes, there is an entry for μάθημα in BDAG, but it is fairly short, giving the same basic glosses as in the Instant Details window along with a few examples in ancient Greek literature. The LSJ, on the other hand, offers much greater details, examples, and five categories of meaning. If you’re going to study ancient Greek literature beyond the New Testament, the LSJ is a must-have tool.

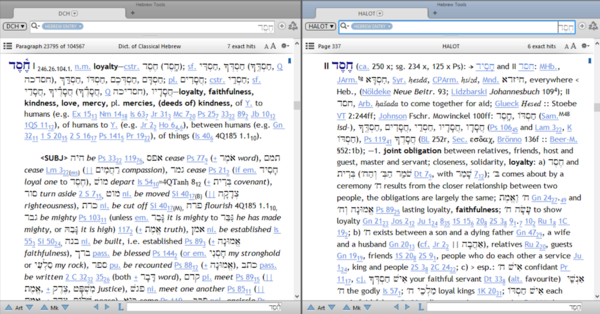

Dictionary of Classical Hebrew (DCH). What the LSJ is to the wide body of ancient Greek literature, the DCH is to Hebrew writings in the ancient world. Originally filling eight volumes in the print edition, the DCH covers not only words in the Hebrew Bible, but also Ben Sira, the Dead Sea Scrolls, and all the other known Hebrew inscriptions and manuscripts.

The DCH is extremely comprehensive covering every word in all extant Hebrew manuscripts. This kind of coverage goes well beyond Hebrew standards such as HALOT or BDB. This resource is invaluable when trying to work with Dead Sea Scrolls, particularly the non-canonical texts of the Qumran writings. And for translating Hebrew inscriptions, which has a much greater vocabulary range than the Hebrew Bible, the DCH is a must. However, since the DCH also covers all content of the Hebrew Bible, too, it is also very helpful as a lexicon to use in parallel with standard Hebrew resources such as HALOT to give better overall understanding to biblical words, especially in their greater literary context. (Compare, for instance, the entry for the frequently occurring חֶסֶד in both HALOT and the DCH—the latter of which offers significantly greater examples from literature outside the Hebrew Bible).

In addition to these two lexical heavy-hitters, a few other lexicons available for Accordance deserve brief mention.

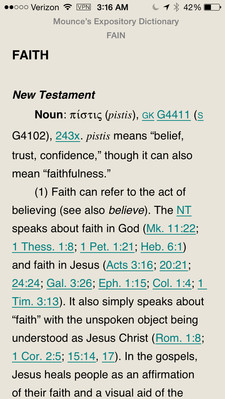

Mounce’s Analytical Lexicon to the Greek New Testament. When I first took Greek, print versions of analytical lexicons were quick and dirty ways to get parsing information for inflected forms of words we couldn’t figure out on our own. Always the educator, William Mounce goes beyond mere word lists to explain the whys of various forms. There’s much to be learned from this volume, even by those who might not ever pick up the traditional analytical lexicon.

Dictionary of Epigraphic Hebrew. This work by J. P. Kang is a must for anyone involved with Hebrew inscriptions of the Iron Age (ca. 1000–586 B.C.E.).

Brown-Driver-Briggs Complete. Many longtime Accordance users may have the abridged version of this standard Hebrew Bible lexicon; however, it is worth upgrading to the complete edition to receive the biblical Aramaic dictionary as well as example links to Scripture references.

My first exposure to lexicons involved lugging around heavy books—sometimes multivolume sets—and searching page after page to find exactly what I was looking for. Whether using these tools on an iPhone, iPad, Mac or Windows computer, there’s never been a better time to have the right lexicon for your particular area of interest or expertise. And having these volumes in Accordance makes tens of thousands of words accessible at a moment’s notice wherever you are.

Consider making these “word books” or any of the many other lexical offerings part of your Accordance library today.